The Revd Canon Edward Nangle (1800-1883) ... a portrait in Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013) Patrick Comerford

I: INTRODUCTION

The Great Famine of 1845 to 1849 left a bitter memory in many parts of Ireland, memories of forced emigration, lost generations, the loss of culture, and the fervour of evangelical missionaries. It is an era that has left us all with a language of myth and prejudice, pejorative words like ‘souper’ and ‘jumper’ that still survive, that are still used, and that still follow families and individuals from one generation to the next.

Today, happily, we live in an age that is less prejudiced and more ecumenical. We have started to answer for the wrongs of our ancestors and to forgive others for the wrongs of their ancestors. Whether our inherited memories are based on myth or fact, they are still real today, and if we are going to ask for forgiveness from each other, then we must be willing to engage in the process that the churches have come to know as ‘Reconciling Memories.’ [1]

Some years ago [1996], Scoil Acla provided a generous opportunity to reconcile these memories, and to explore the truth of those myths and those realities. Two decades ago, during the commemoration of the Great Famine, we were made aware of the need to ask difficult question. But we were not asked to forgive and forget; we were asked to remember and forgive. And if any one person embodies the opportunity to remember, to examine, to forgive, and to retrieve what was good out of it all, then that one person is the man most closely associated with the Irish language and the famine in Achill, Canon Edward Nangle.

The 200th anniversary of his birth provided a valuable opportunity to look afresh at Nangle’s background and story, and the key movements and ideals that shaped his career. In this paper, I hope too to examine, even challenge, some of the popular myths that have arisen about Nangle in the last century and a half. And, finally, I hope to assess Nangle’s impact on the life of Achill Island, so that in a new light he can be claimed properly as part of our common story, whether we are Catholics or Protestants.

The ‘Deserted Village’ at Slievemore on Achill Island (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

II: BIOGRAPHY

Nangle’s family background:

Noreen Gannon, in her account of ‘Achill’s Past,’ says it is not known how large a family Nangle’s father, Captain Walter Nagle, had. [2] In fact, we know quite a lot about the Nangle family, and it makes an interesting story that is worth telling.

The Nangle family of Kildalkey, near Athboy, Co Meath, was what might be described as a strongly Catholic ‘Anglo-Norman’ or ‘Old English’ family from Co Meath, inter-married for generations with similar Catholic families with names like Preston of Gormanston, Cusack, Carney, Drumgoole, FitzSymon, Plunket, Dillon, and Caulfield. Although Sedall plays down the family’s Catholic background, Edward Nangle must have been aware of the celebrated case of an earlier family member, Edward Nangle of Cloondara, Co Longford, who conformed to the Church of Ireland in the 17th century. An army captain, a justice of the peace, and a brother-in-law of the Duke of Ormond’s secretary, Edward Nangle proceeded to have hallucinations in 1660 which Dean Carr of Ardagh was unable to explain. However, a local Catholic priest, Father Patrick Keenan, interpreted Nangle’s experiences as visions of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint Patrick and later the Trinity. Nangle reverted to Catholicism, led a Catholic rebellion and was killed four months later; his experiences led to him being revered by some Catholics as a saint. [3]

In 1689, Captain Walter Nangle’s grandfather and great-grandfather were Catholic Jacobite officers in the army of King James II, and in the Williamite confiscations after the Battle of the Boyne the family lost almost 700 acres. Walter Nangle was the youngest son in a large Catholic family of eleven. Born in 1757, he was brought up a Catholic, his first wife Jane Callan or O’Callan, a daughter of Bartholomew O’Callan of Osbertstown, Co Kildare, was a Catholic too, and they had a large family who were baptised and brought up as Catholics – the sons married Catholic women with names like Bridget Kelly and Cecilia Conolly.

Jane Callan’s sister, Helen Callan, married John Esmonde (ca 1760-1798), a leading United Irishman who was hanged on Carlisle Bridge (now O’Connell Bridge), Dublin, on 14 June 1798. Their children, who were first cousins of the Revd Edward Nangle’s half-borhers and half-sister, included: Sir Thomas Esmonde (1786-1868), MP for Wexford (1841-1847); the Revd Bartholomew Esmonde, SJ, a Jesuit priest and a founder of Clongowes Wood College, and James Esmonde, father of Lieut-Col Thomas Esmond VC (1831-1872), father-in-law of James Charles Comerford (1842-1907) of Rathdrum, Co Wicklow.

The children of Captain Walter Nangle and Jane (Callan) Nangle were:

1, Bartholomew Nangle (1779-1841), baptised in Saint Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, Dublin, on 16 May 1779 (sponsors: Patrick Egan, Elinor Everard). [4] In 1794, he was commissioned as an ensign in the 118th (Fingal) Regiment of Foot and went to England with the regiment. He married Bridget Kelly, and after leaving the army became a Stipendiary Magistrate in Co Tipperary. Their children were baptised Roman Catholics. Bartholomew died on 8 November 1841. [5]

2, Walter Nangle, baptised in Saint Michan’s Catholic Parish, Dublin, on 19 November 1780 (sponsors: Mary Sweetman, William Taaffe). He became a midshipman in the Royal Navy and died at sea. [6]

3, Mary Ellinor Nangle, baptised in Saint Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, Dublin, in March 1782 (sponsors: Gerald Fitzsimons, Anne Cross). [7]

4, Charles Nangle, of Newhaggard House, near Trim, Co Meath, was commissioned in the 20th (Kilkenny) Regiment of Militia. He retired from the army in 1816. He married Cecilia, daughter of Richard Barnewall, of Bloomsbury, Co Meath, and widow of John Connolly of Newhaggard. They had no children. He died a bankrupt on 5 September, 1847. [8]

5, James Nangle, who was commissioned in the 117th (Meath) Militia in 1800. He died unmarried in 1815 or 1816. [9]

6, Jane Nangle, who married Dennis Cassan of Dublin. [10]

It was only with his second marriage in 1790 to Catherine Anne Sall, the daughter of George Sall, a Dublin merchant, that Walter Nangle appears to have conformed, at least nominally, to the Established Church of Ireland. So apart from a large first family of Catholics, Captain Nangle had nine more eight more children, five who died in childhood, and three who survived and who were brought up as Protestants:

7, George Nangle (1791-1871), born on 29 September 1791. In 1816, he married in Cheltenham, Elizabeth Caroline, daughter of Henry Halsey of Henley Park, Surrey. In 1823, he married his second wife, Lucy Elizabeth, youngest daughter of Sir Henry Tichborne, Bt. His eldest daughter, Lucy Elizabeth Nangle (1824-1887), who was born in France, became a nun and died in a convent in Newhall. He died in 1871. [11]

8, William Portland Nangle (1794-1840), baptised in Saint Catherine’s Church of Ireland parish church, Dublin, on 28 September 1794. He went to the West Indies and died unmarried in Jamaica in January 1840. [12]

9, (Revd Canon) Edward Walter Nangle (1800-1883). [13]

10, Frances Emilia Nangle. [14]

11, Frederick Nangle, who died young. [15]

12, Jocelyn Nangle, who died young. [16]

13, Catherine Nangle, died unmarried. [17]

14, Elinor Nangle, who died young. [18]

Walter Nangle’s second wife, Catherine, died in 1808, probably in childbirth. Four years later, on the death of his nephew, James Francis Nangle, Walter succeeded to the family’s claims to the Kildalkey estate, but he never lived there. A year later, in 1813, he married his third wife, Elizabeth, daughter of William Toole of Kilkock, Co Kildare, and they had one daughter:

15, Elizabeth Jane, who on 10 February 1841 married Robert Nicholson of Ballow, Co Down.

By 1827, Walter Nangle was in financially reduced circumstances. He died on 3 July 1843, aged 86.

Edward Nangle was born in 1800, probably on 25 November, and was baptised in Saint George’s Church, Dublin, on 14 December 1800. [19]

Although his great-grandson, Colonel Frank Nangle, believed Edward Nangle was born in 1800, Burke, Leslie, Seddall and others said he was born in 1799. Colonel Nangle believes his ancestor ‘was baptised and brought up a member of the Church of Ireland,’ although the record of his baptism was only recently made available online. Edward may have spent his early years in Dublin, and it is doubtful whether his father ever lived in Kildalkey. His mother died when he was nine, and he was sent away to school when his father married his third time, once again to a Catholic, Elizabeth Toole of Kilcock, Co Kildare. [20]

The difficulties of inter-church marriages at the time should not be forgotten, and two examples illustrate this point. When Father Michael Collins, parish priest of Skibereen, Co Cork, was asked in 1824 what punishment he was liable to if he married a Catholic to a Protestant, he replied, ‘The law is rather strange; there are two punishments, first we are liable to be hanged, and then to a fine of £500.’ [21]

In 1852, Lord de Freyne’s younger brother, the Hon Charles French, married Catherine Maree in front of a Catholic priest. But Lord de Freyne and his next brother, the Revd John French, had no children, and when it became apparent that Charles French was going to inherit the title, questions were raised about the validity of an inter-church marriage performed by a Catholic priest on13 February 1851, the legitimacy of the daughter, Mary, and three sons, Charles, John and William, who born to Charles and Catherine French between 1851 and 1854, and their rights, therefore, to inherit the title. And so, on 17 May 1854, Charles and Catherine were married once again, this time in a Church of Ireland parish church, All Saints’ Church, Grangegorman; eventually, in 1868, the de Freyne title and the estate of French Park passed to the next son born after the second marriage, 13-year-old Arthur French. [22]

It was customary at the time, when there was a Catholic father and a Protestant mother, that the sons were brought up as Catholics and the daughters as Protestants. But for some reason, Walter Nangle decided that the sons of his second marriage should have a Protestant education, [23] and so the young Edward Nangle was sent eventually to Cavan Royal School, where his headmaster was Dr John Moore and where his contemporaries included Thomas Fowell Buxton, the great nineteenth-century Liberal campaigner against slavery, and Robert Daly, the celebrated evangelical Bishop of Cashel. [24]

Trinity College Dublin ... Nangle graduated with a BA in 1823 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

As a student, Nangle admits, he was wild and reckless, but in 1823 he graduated with a BA from Trinity College Dublin, and at first he contemplated a career in medicine. However, his friends urged him to consider a career in the Church, and in Seddall’s words he looked ‘forward to ordination as a means to securing an eligible social position.’ [25] In the summer of 1824, he was ordained deacon by Thomas O’Beirne, Bishop of Meath, for the curacy of Athboy, Co Meath. Soon after, he was ordained priest on O’Beirne’s behalf by George de la Poer Beresford, Bishop of Kilmore. Like Nangle, O’Beirne came from a Catholic background too: he studied for the priesthood in France, but eventually he joined the Church of Ireland, and was successively Bishop of Ossory and Bishop of Meath. [26]

O’Beirne may have been favourably disposed towards finding Nangle his first curacy, given they shared a similar Catholic background. A tolerant and erudite bishop, he was not unusual in being a 19th-century Church of Ireland clergyman with a Catholic family background. But many of those clergy faced bitter criticism and intolerance for having changed their ecclesial allegiance. According to Desmond Bowen, ‘Almost any priest who conformed to the Church of Ireland caused a stir.’ [27] Apart from the case of Lord Dunboyne, the former Bishop of Cork, famous examples from the time include: William Blake Kirwan (1754-1806), a grand-nephew of Archbishop Anthony Blake of Armagh, who joined the Church of Ireland in 1787 and ended his days as Dean of Killala; [28] the Revd TW Dixon, the Catholic curate of Kilmore Erris who later served as Church of Ireland curate in Beaulieu, Co Louth, and Saint Peter’s, Drogheda; [29] David Croly, parish priest of Ringrone, Co Cork, who became a Tractarian and author of a scholarly index of, and dissertation on the Oxford tracts; [30] the Crotty cousins, Michael and William, who had been curates in Birr and became Protestant, Michael a rector in the Church of Ireland and William a Presbyterian minister in Roundstone, Co Galway, during the Famine; [31] the Revd William Phelan from Clonmel, who was offered a seminary place in Maynooth but instead entered TCD as a Protestant, was ordained, and became a close confidante of Primate Beresford; [32] his schoolmates, the brothers Samuel and Mortimer O’Sullivan; [33] and the three Moriarity brothers in Ventry, Co Kerry. [34]

For the Catholic controversialist, Father James Maher, the ‘apostates of Trinity College’ formed a class of their own: ‘The O’Beirnes, the Delacys, the O’Sullivans, the Sheehans, the Phelans, the Moriartys, ad hoc genus omne.’ [35] Yet it would be wrong to categorise all these men as agitating evangelicals; this was certainly not the case with the Tractarian Croly, who remained essentially a liberal catholic until his death. But certainly the emergence and prominence of this group coincides with the ordination of Edward Nangle, a man from a notable Catholic family, and whose Protestant identity only became a matter of controversy with his decision to go forward for ordination in the Church of Ireland. [36]

Early ministry:

Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort, Achill Island (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

At Athboy, Nangle may have come across the Pentlands, a local clerical family who had suffered considerably as a consequence of the 1798 Rising in Co Wexford: the Revd John Pentland, curate of Killanne, was killed on Vinegar Hill on 29 May 1798, while his brother-in-law and rector, Simon Little, lost property valued at £73 during the rising; and Ann Pentland was the wife of the Revd Arthur Colley, curate of Ballycanew during the Rising, when one of his most prominent parishioners was the leading Wexford Orangeman, George Ogle. [37] He certainly developed close friends in Athboy, but Nangle stayed for a few months only. He then moved to Monkstown, Co Dublin, but once again stayed in a curacy for a short time – this time for a mere fortnight. [38]

His next move came at the age of 24 to the Diocese of Kilmore and the small parish of Arva on the borders of Co Cavan and Co Longford, close to Edmund Nangle’s own Cloondara. For two years he was curate to the Rector of Killeshandra, the Revd Andrew McCreight. In Arva he was deeply influenced by the local Primitive Methodists, adopting their Arminian theology which was far more liberal than the Calvinism then dominating evangelical thinking. And one of the key people to influence him there was the Revd William Krause, who was employed as ‘moral agent’ to Lord Farnham and later the preacher at the Bethesda Chapel in Dublin, known as the ‘Cathedral of Methodism.’ An early Lord Farnham had voted against the Act of Union, and in Nangle’s days John Maxwell, the fifth Lord Farnham (1797-1838), a son of Bishop Henry Maxwell of Meath, was described as a ‘man in whom sectarian fanaticism spoiled a good patriot.’ [39]

At Arva, Nangle regularly visited his friends in Athboy, perhaps including the Pentland family, certainly including the Adams family, and at the home of Dr James Adams he met both Dr Neason Adams, who was to join him in Achill ten years later, and his first wife, Elizabeth Warner of Marvelstown House, Co Meath. [40] Once again, however, Edward Nangle, who had difficulty in holding down his first curacies in Athboy and Monkstown, had similar difficulties and he resigned as McCreight’s curate in Arva after two years. Seddall says he resigned due to ill-health, but it appears more likely that in today’s terminology he once again had a nervous breakdown, losing his ability to speak and communicating by gesticulating with his fingers. [41] Despite his health and poverty, Edward and Elizabeth were married in Saint Thomas’s Church in Marlborough Street, Dublin, in 1828. [42]

During his period of recovery in Dublin, Nangle read Christopher Anderson’s Historical Sketches of the Native Irish, and became strongly aware of the injustices which had been done to the Irish people by the concerted efforts to deprive us of the Irish language. [43] Irene Whelan describes this effect as a classical conversion experience, and in the words of his biographer Seddall, Nangle emerged committed to working among the Irish-speaking people of the west. [44]

At this time, the impoverished Nangle was complaining to the highest figures in Church and State that he was without income or clerical employment. This may have been due to his earliest record of being unable to remain long in any one curacy, and also to his close associations with those evangelicals who were then leaving the Church of Ireland to join the Plymouth Brethren: women like Lady Powerscourt and men like Thomas ‘Tract’ Parnell, who urged him to become literary agent for his Religious Tract Society, going from door to door selling penny pamphlets. [45] Many years later, Nangle was to denounce ‘the unscriptural schism of Plymouthism,’ saying it was equal to that of ‘Popery.’ [46]

Nangle visits Achill

An outbreak of famine and cholera swept the west coast of Ireland, particularly Mayo and Sligo in 1831. Evangelical friends asked Edward and Elizabeth Nangle and the Rector of Dumes, near Bantry, Co Cork, the Revd James Freke, to accompany the steamerNottingham from Dublin to Westport with a cargo of Indian meal and to report on conditions along the Mayo coast. At Westport, Nangle made friends with the Rector of Newport, the Revd William Baker Stoney (whose family continued to live in Rosturk Castle until recently), and on Stoney’s prompting, Nangle visited Achill, staying overnight at Achill Sound before crossing on foot when the tide was out, and travelling on horseback to Bullsmouth, Dugort and Keel. [47]

Moved by the temporal and spiritual destitution of the people, Nangle returned to Newport to discuss his feelings with Stoney and the foundations were laid for the Achill Mission. [48] Sir Richard O’Donel of Newport House provided land at Dugort on a long lease with a nominal rent, and Nangle moved to secure support for his mission plans from his old school-friend Robert Daly, by then Rector of Powerscourt. The first committee included Daly, later Bishop of Cashel, Joseph Henderson Stringer, later Bishop of Meath, and the Revd Caesar Otway, and also had the support of Archbishop Power Le Poer Trench of Tuam. The first donation of £390 came from an unnamed woman from a dissenting congregation, [49] perhaps Lady Powerscourt, who lived in Daly’s parish but who had joined Parnell’s sect. [50]

The beach at Dugort ... Edward Nangle and his family settled at Dugort in July 1834 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

The first land was bought in 1833, and after a brief stay in Ballina, the Nangle family settled in Dugort on 30 July 1834. [51] They were soon joined by Nangle’s assistant, the Revd Joseph Duncan, two Scripture readers named Joyce and Gardiner, Alexander Lendrum, his wife and six children, and Dr Neason Adams and his family. [52] The school at Slievemore opened two days before Christmas that year with 43 children attending on the first day, and by the following Sunday there were schools in Dugort, Slievemore, Cashel and Keel, catering for 410 children. [53] With a gift from friends in London and York, a printing press was established a year later in December 1835. [54]

By 1836, the mission was working at Dooega, on Achillbeg, in Ballycroy, and on Clare Island. [55] In 1837, the island of Innisbiggle was rented from O’Donel; that year also saw the first edition of the Achill Missionary Herald and Western Witness. [56] An orphanage was established in 1838, and in the summer of that year, Archbishop Trench visited the island for the first time. [57]

By now, the conflict between Catholic clergy and people on the one hand and Nangle and the mission staff on the other had become extremely violent. A school master and Scripture reader were violently beaten on Clare Island, and were forced to take refuge on the lighthouse before they could escape the island on a coastguard vessel. [58] Francis Reynolds, a coastguard officer who was denounced by name at Mass on several successive Sundays, died as a result of being hit on the head in a house in Keel; John and Bridget Lavelle were cleared of his murder at a trial in Castlebar in Spring 1839, and as a direct consequence of these and other violent incidents, the courthouse was built at Achill Sound in 1839. [59]

John O’Shea and Anne Falvey, in the Spring 1996 edition of Muintir Acla, John Percival in the Great Famine, and Mealla Ni Ghiobuin, in Dugort Achill Island 1831-1861 (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2001, Maynooth Studies in Irish Local History Series), provide accounts of the work of Nangle and the Mission during the Great Famine. I do not propose to repeat what they have written, except to note that in the Spring of 1847 Nangle and the colony were employing 2,192 labourers and feeding 600 children a day, [60] and that the Nangle family, like many rectory families during the famine, [61] suffered their own measure of trauma and tragedy: of the eight children born to Edward and Elizabeth Nangle between 1835 and 1847, five died in infancy, and Elizabeth Nangle, whose mental health had been deteriorating rapidly, died in 1850. [62]

Elizabeth Nangle’s Monument in Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

The children of this first marriage were:

1, Frances Patience Nangle, born on 19 March 1830 in Baggot Street, Dublin. As a girl, she lived in the missionary settlement at Dugort. In September 1850, she married John Wilson, JP, of Daramona House, Co Westmeath. They had one son, William Edward, and three daughters, Elizabeth Dupre, Matilda Dorothea and Beatrice Frances.

2, Henrietta Catherine Nangle, born on 18 December 1831 in Buckingham Street, Dublin. She lived in Dugort and later in Skryne, Co Sligo. On 12 August 1857, she married Dr Francis William Smartt, of Ballymahon, Co Longford. They had four daughters, Elizabeth, Agnes, Frances, Matilda, and four sons, Henry Warner, Edward, Walter and William, all of whom became doctors.

3, Matilda (Tilly) Nangle, born at Downhill, near Ballina, Co Mayo, on 10 October 1833. She died suddenly on 4 June 1852, in Killiney, Co Dublin.

4, A son, born on Achill on 19 April 1835, and died two days later.

5, Edward Neason Nangle, born on Achill on 11 July 1836, and died 23 August that year.

6, George Neason Nangle, born on Achill on 18 October 1837, and died the following month.

7, William Nangle, born on Achill 28 June 1839. He was educated at Portarlington School. On 24 August 1860, he was commissioned in the 15th (East Riding) Regiment of Foot. In 1875, he went with his regiment to India as a captain and served with it at Ahmedbab, Baroda, Deese and Pooma. Five years later he returned to Britain and retired on 1 January 1881, with the rank of Major. After retiring, he lived in Leinster Road, Rathmines, Dublin, where he died unmarried.

8, (Major) Henry Beresford Nangle, born on Achill 20 October 1841. He was named Henry after his maternal grandfather, and Beresford after the then Archbishop of Armagh, Lord John George de la Poer Beresford. He grew up in the rectories in Dugort, and Skreen, and was educated at Portarlington School and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, where he received a prize for landscape drawing. He was commissioned in 1860 and went with the 21st Royal North British Fusiliers to Barbados and then to India, and Burma. He married Isabella Margaret Elizabeth Dobbie, and their children were: Henry Coryndon ‘Cory’ Nangle (1867-1956), Kenlis Edward Nangle (1871-1950), William Gerald Beresford Nangle (1872-1874), Lieutenant-Colonel Montague Claude Nangle (1874-1952) and Isabella Geraldine Nangle (1877-1969), who married Lieutenant-Colonel Ewing Wrigley Grimshaw. The two eldest sons were sent to live with their grandparents in Ireland, and Major Nangle died in Madras in a riding accident on 1 August 1882 and was buried in the graveyard of the Scottish church there.

9, George Edward Nangle, born on Achill 13 April 1844. He probably died in Dublin, in 1872, unmarried.

10, A daughter, who was born on Achill on 10 March 1846, and died at birth.

11, A son, who was still-born at Achill in December 1847.

The foundation stone of Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort – named, perhaps, after the Dublin church where Edward and Elizabeth Nangle were married in 1828 – had been laid by the Bishop of Tuam, Lord Plunket, when he visited Achill Island on 20 September 1849. [63] In April 1851, the mission purchased the lands it had leased from the O’Donel estate. [64]

Nangle after Achill

Surprisingly, although Nangle had settled on Achill in 1834, he only served the parish as rector and vicar for less than two years. In 1850, or perhaps 1851, he was appointed Rector and Vicar of Achill, and was made a canon of Tuam Cathedral in succession to Charles Henry Seymour, who had become Provost of Tuam and was later to become Dean. But Nangle found it easier to work as a missionary than administering a large parish. In 1852, he resigned, left Achill after 18 years working on the island, and moved to Co Sligo, where he became Rector of Skreen in the Diocese of Killala. [65]

He continued to keep an interest in Achill, returning for a three-month period each year, but his relationship with the mission committee and the mission trustees became increasingly fraught and acrimonious. His staying power in Skreen, nevertheless, was greater than any he had exhibited in all other parochial appointments, staying there for 21 years until he retired at the venerable age of 74.

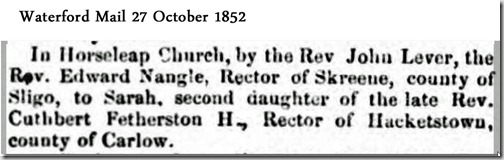

In September 1873, Nangle resigned both as Rector of Skreen and as a trustee of the mission. [66] In 1879, he returned to return to live in Achill briefly, but he then moved to Dublin in 1881 and died on Sunday 9 September 1883, at the age of 84. By then he was a lonely man, almost forgotten by many of his colleagues, and with only his second wife, Sarah*, by his side.

The children of Sarah and Edward Nangle were:

1, Catherine (Kate) Nangle, born on Achill 2 July 1853. She grew up in Skreen, Co Sligo. She went to India and on 28 December 1880in Mysore, she married Hallet G. Batten of the Indian Civil Service, then Assistant Commissioner at Pergu in Burma. They had two daughters and two sons, Mary, Edward (Ted), Helen (Dot), and Henry.

2, Anne Featherstonhaugh Nangle, born 21 December 1855 in Skreen. On 28 May 1896, she married the Revd JH Davidson. They had one son, Douglas, who became an officer in the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and retired as a Lieutenant-Colonel in 1979.

3, Sarah Jane (Jennie) Nangle, born 17 February 1857. On 14 April 1884, she married Major (later Colonel) Charles H. Sheppard of the Indian Medical Service. They had one son, Charles.

4, Edward Cuthbert Nangle, born 7 May 1859, and died in 1942. He became a doctor and moved to East London, South Africa. In the mid-1880s, he married Dorothy Briscoe. They had two sons and a daughter: Dr Edward Jocelyn Nangle, a lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps, who was killed on service in France on 26 September 1916; Dr Milo Nangle, who died in Rhodesia in 1957; Ismay Nangle, who married Cecil Charles Frere in 1911 – their son, Jocelyn, assumed the name Nangle.

Despite two large families by 1882 he had only one surviving son, Dr Edward Nangle, who had moved to Africa, while only two of his daughters were married and still living in Ireland. He was buried in Dean’s Grange Cemetery, Dublin, and his funeral was conducted by the Revd John Lynch of Saint John’s, Mounttown – a church now used by supporters of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre for their Tridentine Mass. [67]

Edward Nangle’s Monument in Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

III. ASSESSING NANGLE’S WORK

There are four claims about Nangle’s work that deserve critical re-examination:

● Claims about the effects of his work and his polemics on Catholic-Protestant relations in Achill and throughout Mayo;

● Claims about the relation of his work to the ministry of the Church of Ireland in Achill before his arrival and after his departure;

● The claims made on behalf of Nangle regarding his contribution to the survival of the Irish language in this area; and

● The claims or allegations that Nangle was involved in ‘souperism’ in Achill.

1. Nangle and Catholic-Protestant relations today

The bell at Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

It has been argued that the nature of Nangle’s polemics and the violent tones of his attacks on Catholicism have left a negative and lasting legacy. According to Irene Whelan, Nangle’s Achill missionary project ‘left its mark on Protestant-Catholic relations generally in Co Mayo.’ [68] However, it must be remembered that others contributed to this debate at the time with similar, virulent language that would be regarded as highly offensive today, and these included Catholics and Protestants.

On the Protestant side, they were men like Stoney, who first introduced Nangle to Achill. Between 1822 and 1830, Stoney made himself an unpopular figure while he was curate of Kiltullagh, Co Roscommon, with his controversial claims to making over 100 converts from Catholicism in that parish. He continued this aggressive approach as Rector of Burrishoole or Newport, entering into an unseemly war of pamphlets with Father James Hughes, parish priest of Newport, in January 1837, and as Rector of Castlebar from 1839 to 1872. [69]

On the Catholic side, Nangle met his foil in Archbishop MacHale, who was equal in his vigour and his rhetoric in challenging his opponents, whether they were Catholic or Protestant. Writing to Lord John Russell on the eve of Pentecost 1835, MacHale spoke of ‘the demon of fanaticism and religious rancour,’ ‘fanatics,’ ‘spiritual poison,’ and money coming from ‘credulous dupes of imposture.’ And he claimed the mission committee spoke of 198 Achill islands with a population of 150,000 ‘who worship a stone for their god.’ He was challenged to prove or rescind these claims, but never did either. [70] Later that year, in a letter from Achill, MacHale boasted he had succeeded in crushing out the infant mission with its ‘fraudulent fanaticism’ and claimed ‘its buildings, now unfurnished, are like the Tower of Babel, a monument to the folly and presumption of the architects.’ [71] Obviously, MacHale could not substantiate these claims either: the mission flourished and its buildings stand to this day.

In a letter to the Freeman’s Journal, MacHale said he had sent Father James Dwyer to Achill as parish priest ‘to arrest the current of vice and immorality that has been turned into the island.’ Dwyer engaged in a bitter and relentless battle with Nangle, and in letters to the English press he denied Nangle’s school and orphanage existed. If MacHale was critical of Nangle raising funds in England, he had no qualms about visiting England himself to raise money to support Dwyer’s work. [72]

Other Catholics were more kind in their assessment of Nangle, including John Patrick Lyons of Belmullet, the Dean of Killala, who was MacHale’s archenemy within the Catholic Church in Co Mayo. [73] After the explorer’s wife, Lady Franklin, met Lyons at dinner, she reported the dean describing Nangle in these words: ‘He is an excellent man, and he is doing a great deal of good to the poor people of Achill, among who, with a most praiseworthy philanthropy, he has buried himself.’ [74]

Apart from his appreciation of Nagle, Lyons, a devoted Irish scholar, also appears to have had a high regard for the Revd Thomas de Vere Coneys, who had worked as Nangle’s assistant in Dugort from 1837 to 1840. Coneys was appointed the first Professor of Irish at Trinity College Dublin in 1840, and in 1842 and 1843, during a visit to Rome, Lyons informed Coneys of the existence of Irish manuscripts in the Vatican archives. [75]

If Nangle had his Catholic critics, then, it should not be forgotten, he also had his Anglican critics. They included the future Bishop Edward Stanley of Norwich, although Nangle could retort that Stanley spent less than two whole days on the island. [76]

Even Seddall and Bishop Plunket conceded that Nagle could be too strong in his language and his choice of phrase. Plunket said he was

headstrong in forming his opinions, stubborn in holding them, and harsh in giving them expression. Any conclusions to which he himself had arrived seemed to him so incontestable that he was often slow to give credit for sincerity to those who might happen to differ from him, and under an exaggerated sense of what he deemed ‘faithfulness,’ he too often pronounced judgment upon others with undue haste. [77]

Seddall too conceded that when speaking plainly and clearly, Nangle’s language was ‘undoubtedly strong’ and he admits that Nagle was seen by some of his fellow Anglicans as ‘a firebrand, a fanatic and a disturber of the peace.’ [78]

Much of Nangle’s aversion to Catholicism may have been derived from his own Catholic background, and it certainly was not shared to the same degree by many of his colleagues such as Coneys, who had developed a friendship with Lyons, or Charles Seymour, Nangle’s predecessor as Rector and Vicar of Achill. Seymour was the son and grandson of clergymen. His father, the Revd Joseph Seymour, grew up in an Irish-speaking clerical family in Clifden and Boyle. In one parish, the previous incumbent was threatened with the loss of his living because of a dwindling Protestant population; but in an incident that might have inspired a scene in The Quiet Man, which the bishop visited his parish, his neighbours filled the church for the rector, with the approval of the parish priest, in the hope that the bishop would allow him to stay on. When Joseph Seymour died in 1850, he was mourned equally by his Protestant and Catholic neighbours and parishioners. [79]

And in defence of Nangle, it must be said that many of the most bigoted views ascribed to him are not his but those of Seddall, interwoven through his biography without ascription or acknowledgment in a way that would force any history tutor to fail it today if it were offered as an essay by a first-year student.

Nangle’s principal criticism of Catholicism centres on transubstantiation, or rather his interpretation of transubstantiation. Since then, happily, the two Churches have much closer to an understanding of what is meant as the mysteries of the Eucharist are celebrated. [80] Nevertheless, it much be said that Nangle’s pillorying of beliefs so sacred to a sister Christian community is indefensible and, at points – for example, his woodcut of a mouse eating the host – are completely offensive. However, this is not Nangle’s legacy.

Today in Achill, as in Ireland, the religious enmities of the past have been eased by ecumenism and softened even by secularisation. On 24 September 2011, the Catholic and Church of Ireland spiritual heirs of MacHale, Archbishop Michael Neary, and of Nangle, Bishop Patrick Rooke and the Revd Val Rodgers, held a joint service at Saint Thomas’s in memory of the people buried in 190 unmarked graves in the mission’s churchyards and graveyards, and to honour all who died in Achill during the 19th century, particularly during the Great Famine. Nangle’s legacy today is the invitation on the gates below his church in Dugort, welcoming all Christians, whatever their denomination, to Communion at the table in Saint Thomas’s.

2. Nangle and parochial ministry in Achill

Inside Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

The second claim I wish to examine is the dependency of the Church of Ireland parochial ministry in Achill on Nangle’s work. It has been claimed by Seddall, and repeated by others, that Nagle was the first clergyman of the Church of Ireland to pay attention to Achill. Seddall makes the extraordinary claim that before Nangle’s missionary work began in Achill – in other words, before 1834 – a helpless old clergyman in Newport received £100 a year from the parish of Achill which he never visited, and that the Protestant coastguard on the island had to a local Catholic priest to baptise his child. [81] The Revd George McIlwaine, Rector of Saint George’s, Belfast, who visited Achill in 1849, claimed that 17 years earlier, in 1832, there was not a solitary member of the Church of Ireland in Achill. [82]

The first recorded clergyman in Achill in modern times was the Revd John Horsley Beresford, who was ordained deacon and priest in 1803 by Bishop William Bennett of Cloyne and was soon after appointed Vicar of Burrishoole, Kilmeena and Achill by his father William Beresford, Archbishop of Tuam and first Lord Decies. The younger Beresford was a pluralist, holding the parish of Granard from 1805, and the parishes of Aherne and Ballynore in the Diocese of Cloyne from 1806, and he was non-resident in the Mayo parishes of Newport and Achill by 1808 and resigned the following year. In 1819, he succeeded to his father’s peerage, and although he remained a canon of Lismore Cathedral, Co Waterford, until his death in 1855, subsequent family histories fail to record his clerical career. [83]

Lord Decies’s successors, Canon Thomas Mahon (1809-1825) and the Revd John Galbraith (1825-1830), were faithful rectors, however, resigning only to move to other parishes. Curiously, Nangle must have been aware of these clergy in Achill as he named one of his sons after the Archbishop’s family, Henry Beresford Nangle. The parishes of Newport and Achill were one until 1830, when Galbraith, Archbishop Trench’s cousin, resigned to become Vicar and later Provost of Tuam. [84] In 1830, the parishes were separated and Stoney, then aged 36, became Rector and Vicar of Burrishoole, while the slightly older Charles Wilson, a clergyman’s son, became Rector and Vicar of Achill – slightly older in so far as Wilson was 39, eight years older than Nangle, but hardly an old man at 41 when Nangle first visited the island in 1831, or at 42 in 1832, at the time of McIlwaine’s claim. In 1837, there was no church on the island, but although the site of the church and rectory for Achill’s parish was off the island at Achill Sound, it should be noted that in 1837 Wilson was holding services in private houses on the island. Wilson appears to have been a diligent rector. In 1840, he was made Prebendary of Faldown, becoming a canon of Tuam Cathedral, hardly a promotion earned by a lazy or negligent pastor. And at the height of the famine, in 1847, he died a worn-out man, perhaps of famine disease, at the age of 56. [85]

On the other hand, Bowen claims that by 1879 Nangle was having difficulty in finding incumbents for Achill and Dugort. [86] Manifestly, this was not so: in 1879, the Revd Charles Le Poer Trench Heaslop, who had worked in Renvyle, Co Galway, and in Belmullet, Co Mayo, came to Achill as Rector, and when he resigned in 1881 he was quickly succeeded by the Revd Michael Fitzgerald who had been curate of Berehaven, Co Cork; [87] and in 1879, the Revd John Bolton Greer, the curate of Achill, was appointed Rector of Dugort, remaining there until 1886, two years after Nangle’s death. [88]

The Church of Ireland did not begin in Achill with Nangle’s work: there had been a parochial ministry there long before his arrival; nor did the parishes of Achill and Dugort suffer from his departure; rather they attracted men of the highest calibre to work there. [See Appendix]

3. Nangle and the Irish language

Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

The third area of Nagle’s life that can lead to some conflicting claims is his attitude to the Irish language. Sometimes the claims can be extraordinary: on the one hand, that Nangle rescued the Irish language from extinction in Achill and on Innisbiggle; on the other hand, that Nangle and missionaries like him were only using the Irish language as a clever ploy to beguile naive peasants.

Undoubtedly, Nangle had a deep and rich appreciation of the Irish language ever since his reading of Anderson’s Historical Sketches of the Native Irish. [89] And, unquestionably, the printing press, with its typefaces in Irish and the mission schools played valuable roles in fostering, promoting and ensuring the survival of the Irish language: William Neilson’sIntroduction to the Irish Language, printed at the Achill Mission in 1845, is still used by Irish students today; Mr and Mrs Hall, who are best remembered for their criticism of the Achill Mission in 1842, praised the promotion of the Irish language in Dugort in 1849. [90]

But the credit for this promotion of Irish does not rest with Nangle alone. Many of the mission staff, both clergy and laity, were able and fluent in our native tongue. Michael MacGreal, the first teacher employed in the mission school in Slievemore, was an enthusiastic lover of his native tongue, and loved to recite poetry in Irish, especially the Oisín cycle. He also wrote his own poems, and his hymns in Irish were used for many decades after. [91]

Seymour, rector and vicar of Achill throughout the crucial famine years of 1847 to 1850, was brought up in an Irish-speaking clerical household in the west of Ireland. [92] Coneys, who came to work with the mission in 1837, had previously worked from 1832 until 1835 with Henry Beamish as curate of Trinity Chapel, the Irish-speaking congregation attached to Saint Giles in London, and when he left Achill in 1840 it was to take up his appointment as the first-ever Professor of Irish at TCD. [93] William Kilbride, who officiated at the funeral of Nangle’s wife Elizabeth in 1850, and later at the funeral of their daughter Matilda, distinguished himself in Irish as a student, being a Bedell scholar at TCD. He worked as an Irish-speaking curate in Errismore and Clifden, Co Galway, before coming to Achill as a curate in 1852; he went on to spend 43 years as Rector of the Aran Islands, and in 1863 he translated the Psalms into a metrical version in Irish. [94] Other Bedell scholars included Robert O’Callaghan, who was a curate in Achill from 1857 to 1861, and James O’Connor, who was curate from 1910 to 1912, and Canon James Bartley Shea, Rector of Burrishoole 1927-1945. [95]

None of this should take away from the fact that apart from his fluency in Irish, Nangle had a number of other languages, and was all intents a man of culture: he could play the violin with virtuosity, he knew his Haydn and Mozart, his watercolour of Dugort Strand owned by the late Mrs Violet McDowell of Gray’s Hotel shows he was an accomplished artist, and through his friend Alexander Dallas he would have been familiar with the works of the poet Byron.

But in regard to the Irish language, as Desmond Bowen points out, Archbishop Trench of Tuam was loathe to ordain any man to work in the diocese who did not speak Irish. So, a previous rector, the Revd Gary Hastings (now Archdeacon Gary Hastings), with his love of the Irish language, was continuing a long tradition among the clergy of Achill, a tradition that predates Nangle, and that survived long after him.

4. Nangle and the myth of ‘Souperism’

The fourth area of criticism of Nangle’s life, and probably the most enduring one, is the allegation that he and the mission engaged in ‘Souperism.’ The term ‘souperism’ is pejorative and implies either that Nangle favoured Protestants first when it came to handing out relief aid and food during the Famine, or that food aid was used during the Famine to tempt or entice people to abandon their Catholicism and to become Protestants.

The principle foundation for allegations of ‘souperism’ against Nangle and the mission arise from the visit of Mr and Mrs SC Hall to Achill in 1842, and their subsequent report of what they saw at Dugort in a large and widely-read book, Ireland, Its Scenery and Character. The Halls were disparaging in their account of the mission, and the damaging publicity their book brought to the mission was compounded further with the publication of Asenath Nicholson’s account of her visit to the island in 1845. [96]

Nangle said the Halls were hardly in a position to evaluate his work having visited the island for less than two days, and the mission settlement for merely a few short minutes. We should remember too that that first visit to Achill by the Halls came a good four or five years before the Great Famine reached Achill, and Mrs Nicholson’s visit a year or two before the Famine reached the island.

What is often forgotten is that the Halls returned to Achill once again in 1849 and paid tribute to the work of the mission staff during the crisis months of the famine, saying they were ‘indefatigable in their efforts to raise funds’ and ‘distributed with no sparing had to those who must otherwise have perished.’ [97] By 1853, the Halls were trying to avoid being drawn into comment on the island and advised visitors to make their own judgment; but by then Nangle had left Achill, and the allegation of ‘souperism’ dogged him for the rest of his life.

Perhaps if we listen to the people of Achill rather than the Halls we might be better able to assess the nature of Nangle’s relief work. In March 1848, hundreds of people from Dooniver, Bullsmouth and Ballycroy approved a declaration of thanks to Canon Nangle for supplying them with potatoes and turnips from one of the mission farms in Inishbiggle; without the food, they said, they would have starved. As Anne Falvey writes, ‘Despite the criticisms heaped upon him, we can only surmise how much more tragic the situation would have been but for the charitable efforts of Nangle and hundreds of generous donors.’ [98]

Looking from Bullsmouth across to Inishbiggle (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

IV. NANGLE’S LEGACY

So what then was Nangle’s legacy when he left Achill in 1852? What did he leave behind that had a lasting effect on life on the island? I would like to point to some of the areas in which Nangle had a lasting and positive influence on life in Achill.

1. Catholic life on the island. It is ironic, and it might not be appreciated by Nangle today, but one of the interesting consequences of the Achill Mission was the reinvigoration of Catholic life on the island. Before Nangle’s arrival, there were two priests working on the island, with one small church near Kildavnet. But Nangle posed a real challenge to MacHale and his neglect hitherto of the pastoral needs of the islanders.

As Irene Whelan has pointed out, at the beginning of the 19th century, ‘Mayo was not especially renowned for its Catholic character and Achill was one of the most neglected areas of the west with reference to clerical manpower.’ [99] Without the attention Nangle and his colleagues paid to Achill, it is unlikely that MacHale would have sent the Vincentian missionaries, Villas and Rinolfi, to the island with the hope of launching a ‘Second Counter-Reformation,’ or the Franciscans to Bunacurry to start a monastery and open a school, giving Achill not one, but two competing, educational systems. [100]

2. Land reform. Nangle and the mission committee first took a long lease on the O’Donel estate in Achill and on Inishbiggle, and subsequently bought out the estate. Sir Richard O’Donel himself admitted at one stage that his Achill estates had provided him with little income, and he certainly was unwilling to invest any of his dwindling fortune into helping his tenants. Had the Achill mission not bought out the leases when the O’Donel estate collapsed after the Famine, it is difficult to imagine the plight that would have befallen the people of the island. But by then Nangle and his committee had purchased the interest of the tenants occupying 2,000 acres of land, enclosed 200 acres, and reclaimed 70 acres of wild moor; tenant farmers were given viable holdings, crop rotation was introduced for the first time, and many of the poorest tenants living on crowded stripes of land were found new holdings on Inishbiggle. [101]

3. Tourism. The visits of the Franklins, the Halls and Mrs Nicholson, and the debates about Achill and the mission in the British press and in parliament drew great attention to the island. Soon, Achill was on the itinerary of every fashionable tourist in the west of Ireland. In 1839, the Slievemore Hotel was built, and a year later hotels were built at the Sound and in Newport. By 1840, the traveller could leave Dublin in the mail on a Thursday evening, sleep in Newport on Friday, reach Achill Sound on Saturday, and worship in Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort, on Sunday morning. [102] It is difficult to imagine how great the obstacles to travel were in those days, and Nangle can certainly be credited with introducing tourism to Achill. [103]

4. Health Care. It should be remembered that Nangle’s interest in mission work was nurtured while he was being nursed back to health by Neason Adams, and he was first brought to Achill because of an outbreak of cholera as well as famine. The health care provided by Adams, the ‘Saint Luke of Achill,’ is one aspect of the mission that has never been criticised, and Adams has never been accused of any kind of ‘Blue Card Souperism.’ Under the supervision of Dr Adams and his successor, Dr Croly, a small cottage-style hospital was maintained, and their dispensary offered free attention and free medicine to all without question. [104]

5. The infrastructures. Achill benefitted in other ways too from the work of the mission. When Nangle first visited the island in 1831, he reported there was no road from Achill Sound to Bullsmouth and Dugort. And in addition, there was no pier at Dugort, so that in a famine year when there was a bumper catch of fish it could have been greater but for the fact that the boats had to land their catch on the strand at Dugort. Because of the interest of the mission, the first pier was built at Dugort, as well s the first courthouse at Achill Sound, and the infrastructures of the island began to develop.

6. Employment and population. The mission, agricultural reform, building work, roads, the pier, tourism all helped the development of the economy on the island, and ensured that emigration did not hit Achill as badly in the 19th century as it might have had without the mission. Ironically, there was proportionately greater emigration from the Protestant population of Achill. In the second half of the 19th century, the Rector of Achill, the Revd Michael Fitzgerald, gave some idea of the scale of Protestant emigration from the island when he wrote:

During the months of April and May 1883, and within the last ten days, I have lost by the rapid tide of free emigration to Canada, the United States of America, and Australia, forty-two members of my flock, thirty-six of whom belong to Achill Sound, and six to the island of Inishbiggle. [105]

A sympathetic evangelical commentator says ‘the encouraging thing about the emigration was that those who left were anxious to take with them the Irish New Testament so they could share the Word of God with their fellow countrymen in their distant homes.’ [106] An so it may be an ironic consequence of the mission that due to stalling Catholic migration, there are, proportionately speaking, more Catholics living on the island today than Nangle might have anticipated.

7. Overseas mission. One other legacy that Nangle has left is one not so much to the island but to the Church of Ireland as a whole – a socially aware engagement in missionary work. In many of the years before the Famine, the Hibernian Missionary Society (CMS) sent few missionaries overseas: in 1825, 1826, 1827, 1829, 1833, 1839, 1840, 1843, 1844 and 1845, only one man from Ireland went overseas each year on behalf of the CMS; in each of the years 1828, 1830, 1831, 1834, 1836, 1838, 1841 and 1842, no men from Ireland went abroad as CMS missionaries. [107]

In today’s environment, it is difficult to imagine that missionary work was neglected in all the Reformation Churches from the beginning of the 16th century. Modern mission societies owe much to their inspiration to the Moravians, who were the first to engage in mission work in India and among the Native Americans. Bishop Plunket of Tuam, in his introduction to Nangle’s biography, admits that one of the strongest criticisms that could be made of the Church of Ireland was its neglect of missionary work. [108] The Irish branch of CMS was founded only in 1814, and Nangle says ‘I had long determined to devote myself to missionary work among the native Irish on the plan of the United Brethren,’ that is, the Moravians. [109]

The Moravians were socially-aware, philanthropic and mild-mannered, and challenged the prevailing, harsh Calvinist view of the time that preaching the Gospel to non-Europeans, or even non-Anglo-Saxons, was like casting pearls before swine. [110] Nangle’s mission work among the Irish-speaking people of Achill must be seen in the overall context of English-speaking Anglicans with a social conscience deciding to reach out primarily to the non-English-speaking parts of the Empire in the first half of the 19th century. [111]

V. CONCLUSIONS

The Revd Canon Edward Nangle (1800-1883) ... a portrait and memorial at the chancel arch in Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

So what can we say about Nangle that has not been said over and over again? What can be said that helps to put him in a new light? We can say that Nangle’s Catholic background, coming from a family in which he had a large number of Catholic half-brothers and half-sisters, may have forced him to display a zeal for all things Protestant in an effort to secure a post in the Church of Ireland after at least one nervous breakdown.

We can say that he came from a large family, but died a sad and lonely old man, who was buried not in his ‘Happy Valley’ of Achill, or in Skreen, where he spent his longest time ever as a priest in the Church of Ireland, but in Dean’s Grange Cemetery, Dublin, in a grave that is largely forgotten. He himself, at the time of his death, was largely forgotten by many of his former colleagues, and had become an embarrassment to others.

But if he was largely forgotten at the time of his death, his legacy has been largely forgotten today. It was not a legacy of harsh rhetoric, bigoted polemics, or a narrow interpretation of evangelicalism. We must remember that his language, no matter how reprehensible it is today, was the language of the day, and was used by all, including MacHale and Nangle’s own critics within the Anglican Churches.

The beach at Keel ... Edward Nangle died far from his ‘Happy Valley’ of Achill (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

His real legacy, I believe, lies in the social aspect of his mission. He was moved from the beginning to help the people of the west of Ireland in their poverty and in their physical needs.

The South African mission theologian, David Bosch, condemns the sort of evangelism that is carried out without any reference to the wider world it is the sort of evangelism with

no reference whatsoever to any positive attitude to, or involvement in the world. There is no indication that people’s personal and spiritual liberation should have implications on the social and political front. There is a sharp break here; the liberation process is truncated.

These are condemnations of today’s conservative evangelicalism that do not apply to Nangle. Bosch goes on:

Whenever the Church’s involvement in society becomes secondary and optional, whenever the Church invites people o take refuge in the name of Jesus without challenging the dominion of evil, it becomes a countersign of the Kingdom. It is then not engaged in evangelism but in counter-evangelism. When compassionate action is in principle subordinated to the preaching of a message of individual salvation, the Church is offering cheap grace to people and in the process denaturing the Gospel.[112]

Nangle did not meet the poverty and the people of Achill with the cheap grace offered by some conservative evangelicals today. Rather, his work and his action place him firmly in the school of evangelicalism which eventually became concerned with the ‘Social Gospel’ and from which grew the modern ecumenical movement.

APPENDIX [113]

RECTORS, VICARS AND CURATES OF ACHILL

Rectors and Vicars of Burrishoole, Kilmeena and Achill

1803-1809: John [Horsley] de la Poer Beresford

1809-1825: Thomas Mahon

1825-1830: John Galbraith

Rector and Vicars of Achill:

1803-1809: John [Horsley] de la Poer Beresford

1809-1825: Thomas Mahon

1825-1830: John Galbraith

1830-1847: Charles Wilson

1847-1850: Charles Henry Seymour

1850-1852: Edward Nangle

1852-1872: Joseph Barker

1872-1878: Thomas Stanley Treanor

1878-1879: Edward Browne Dennehy

1879-1881: Charles le Poer Trench Heaslop

1882-1897: Michael Fitzgerald

1898-1938: Thomas Boland

1938-1939: Patrick Kevin O’Horan

1939-1942: Walter Mervyn Abernethy

1942-1945: Frederick Rudolph Mitchell

1945-1953: George Harold Kidd

1953-1956: William Fitzroy Hamilton Garstin

1956-1960: George Sidebottom

1964-1969: Olaf Vernon Marshall

1969: Achill grouped with Westport Union

1969-1970: John Coote Duggan (rector).

1969-1971: Louis Dundas Plowman, curate, resident in Achill Rectory.

1970-1972: John Barnhill Smith McGinley (Rector).

1972-1973: Louis Jack Dundas Plowman, bishop’s curate

1973-1979: Herbert Friedrich Friess

1979-1982: Achill served by the Rector of Wesport, the Revd Noel Charles Francis, and the Vicar of Castlebar (1981-1984), the Revd GR Vaughan.

1984-1991: Henry Gilmore, Rector of Castlebar

1991-1995: William John Heaslip

1995-2009: Gary Hastings

2009-present: Val Rogers

Perpetual Curates, Incumbents, of Dugort, Saint Thomas’s

1851: Edward Nangle

18??-1861: Nassau Cathcart

1861-1867: William Skipton

1867-1871: George Abraham Heather

1872-1878: John Hoffe

1879-1886: John Bolton Greer

1886-1890: Vacant

1890-1914: Robert Lauder Hayes

1914-1924: Bertram Cosser Wells

1924: Joined to Achill

Curates of Achill:

1834-1851: Edward Nangle

ca 1837: Joseph Baylee

1837-1840: Thomas de Vere Coneys

1842-1852: Edward Lowe (also curate of Dugort 1852).

1844: John French

1852: Joseph Barker

ca 1852: James Rodgers

1852-1853: William Kilbride

1857-1861: Robert O’Callaghan

1861-1863: Abel Woodroofe

1867: George Abraham Heather

1870-1872: John Hoffe

1873-1876: Robert Benjamin Rowan

1877: Charles Cooney

1879: John Bolton Greer

1910-1912: James O’Connor

1969-1972: Louis Jack Dundas Plowman

Curates of Dugort:

1852: Edward Lowe

Footnotes and References:

[1] See, for example, Alan D Falconer (ed), Reconciling Memories (Dublin: The Columba Press, 1988); I have used the term ‘Catholic’ throughout this paper rather than ‘Roman Catholic’ because I do not want to cause offence to some, and hope others will accept those reasons.

[2] Noreen Anne Gannon, Achill’s Past (privately published, Achill, 1980), p 10.

[3] See Raymond Gillespie, ‘The Religion of Irish Protestants,’ p 91 and p 245 n 15, in A Ford, J McGuire and K Milne (eds), As By Law Established: The Church of Ireland Since the Reformation (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 1995).

[4] http://churchrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/details/fd27b50145642

[5] http://www.nanglemedieval.com/Nangle%20Kildalkey%20Branch%20-%2037.pdf

[6] http://churchrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/details/7c740d0230678

[7] http://churchrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/details/c7197e0146628

[8] http://www.nanglemedieval.com/Nangle%20Kildalkey%20Branch%20-%2037.pdf

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid.

[11] http://www.nanglemedieval.com/Entire%20Book.pdf

[12] http://churchrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/details/205d2f0052327

[13] http://www.nanglemedieval.com/Entire%20Book.pdf

[14] http://www.nanglemedieval.com/Nangle%20Kildalkey%20Branch%20-%2037.pdf

[15] ibid.

[16] ibid.

[17] ibid.

[18] ibid.

[19] http://churchrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/details/4e8ee60068539 Seddall assumes Nangle was born in Kildalkey, but this baptismal record, TCD records and Leslie’s typescript list of the Tuam diocesan clergy in the RCB Library, Dublin, show he was born in Dublin. David Crooks’s revision of Leslie continues to offer 1799 as the date of Nangle’s birth, see JB Leslie and DWT Crooks, Clergy of Tuam, Killala and Achonry(Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation and The Diocesan Council, Tuam, Killala and Achonry, 2008), p 492.

[20] Burke’s Landed Gentry of Ireland (1958 ed), s.v. ‘Nangle of Kildalkey,’ pp 514-515; FE Nangle, A Short Account of the Nangle Family (privately published, Ardglass, 1986), pp 12-13, 25, 46 n 33; Henry Seddall, Edward Nangle: The Apostle of Achill, A Memoir and History (London: Hatchards, Picadilly, Dublin: Hodges Figgis, 1884), pp 31-32. Seddall is quite misleading and Colonel Nangle’s work romantics the family’s background and circumstances.

[21] Parliamentary Papers, 1825, VII (20), 369.

[22] See Debrett’s Peerage, various editions, s.v. de Freyne; the three children born between 1851 and 1854 are not mentioned in Burke’s Peerage.

[23] He may have made this decision with the death of his second wife, Catherine, in order to place their sons in a boarding school; Edward Nangle went to four schools, but Seddall only mentions one school, and I wonder whether the three previous schools were Catholic.

[24] Seddall, pp 22-27.

[25] Seddall, p 29.

[26] Desmond Bowen, The Protestant Crusade in Ireland, 1800-1870 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1978), p. 144; JB Leslie, Ossory Clergy and Parishes (Enniskillen: RH Ritchie, 1933), pp 34-36; Henry Cotton, Fasti Ecclesiae Hibernicae (Dublin: Hodges and Smith, 1848, vol ii), pp 288-289.

[27] Bowen (1978), p 144.

[28] ibid, p 144; JB Leslie, Killala Biographical Succession List (1938, Ts 61/2/9, RCB Library, Dublin), f 21; Alan Acheson, A History of the Church of Ireland, 1690-1996(Dublin: The Columba Press/APCK, 1997), p 79.

[29] JB Leslie, Killala Ts, f 65; JB Leslie, Armagh Clergy and Parishes (Dundalk: William Tempest, 1911), pp 147, 244; JB Leslie, Supplement to Armagh Clergy & Parishes(Dundalk: W Tempest, 1948), pp 88-89; Bowen (1978), p 144.

[30] Bowen (1978), pp 148-149.

[31] ibid, pp 150-153.

[32] ibid, pp 58-61.

[33] ibid, pp 117-121.

[34] ibid, p 205.

[35] ibid, p 114.

[36] Seddall, pp 31-32.

[37] JB Leslie, Ferns Clergy and Parishes (Dublin: 1936), pp 73, 93, 115-116, 213, 233; JB Leslie, Leighlin Ts (RCB), vol ii, f 362.

[38] Seddall, p 32; JB Leslie, Tuam Biographical Succession List (1938, Ts 61/2/15, RCB), ff 76-77; Leslie and Crooks, p. 492. Interestingly, neither Nangle nor this short-lived curacy is not listed in EJR Wallace (ed), Clergy of Dublin and Glendalough (Belfast: The Ulster Historical Foundation and Dublin: Diocesan Councils of Dublin and Glendalough, 2001), see pp 143, 917.

[39] Seddall, pp 32-36; Bowen (1978), pp 68-69; Burke’s Peerage, various editions, s.v. Farnham.

[40] Seddall, pp 38-40.

[41] ibid, p 41.

[42] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 76.

[43] Seddall, p 43.

[44] Irene Whelan, ‘Edward Nangle and the Achill Missions, 1834-1852,’ in R Gillespie and G Moran (eds), A various country: Essays in Mayo History, 1500-1900 (Westport: Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta, 1978), p 119; Seddall, p 43.

[45] Seddall, pp 44-45; Parnell’s brother, William Parnell of Avondale, was grandfather of Charles Stewart Parnell; see Burke’s Peerage, various editions, s.v. Congleton.

[46] Edward Nangle, Revision of the Prayer Book (Dublin: Robert T White, n.d.), p. 8.

[47] Seddall, pp 46-53.

[48] ibid, p. 54.

[49] ibid, 58-59.

[50] See Bowen (1978), pp 65, 75-75.

[51] Seddall, p 60.

[52] ibid, p 61. Other family names associated with the mission at an early stage included Hoban, McDowell, McHale, McNally, McNamara, Sheridan and Sweeny; family tradition says that Thomas McHale and David McHale, the Scripture readers, may have been brothers and may have been related to Archbishop MacHale.

[53] Seddall, p 36.

[54] ibid, p 38.

[55] ibid, p 88.

[56] ibid, pp 88, 94.

[57] ibid, pp 110-111.

[58] ibid, pp 89 ff.

[59] ibid, pp 113-177.

[60] ibid, p 161.

[61] See Robert McCarthy, ‘The Role of the Clergy,’ in Patrick Comerford, et al, The Great Famine: A Church of Ireland Perspective (Dublin: APCK, 1996), pp 7-12.

[62] Anne Falvey, ‘Reverend Edward Nangle: Visionary or Pragmatist?’ Muintir Acla, Issue 3, Spring 1996, p 36.

[63] Seddall, p 173.

[64] ibid, p 190.

[65] Leslie, Tuam Ts, ff 76-77.

[66] ibid, f 77; Leslie, Killala Ts, f 112; Seddall, p 340.

[67] Seddall, pp 340 ff; Leslie, Tuam Ts, pp 76-77; Burke’s Landed Gentry of Ireland (1958 ed), p 515.

[68] Whelan, p 113.

[69] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 86.

[70] Seddall, p 72.

[71] ibid, p 73.

[72] ibid, pp 113-114.

[73] See Desmond Bowen, Souperism: Myth or Reality, a Study in Souperism (Cork: Mercier Press, 1970), pp 55-64; Bowen (1978), p 203.

[74] Quoted in Seddall, p 76.

[75] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 78; Leslie and Crooks, p. 303; Bowen (1970), p 57; Bowen (1978), p 203.

[76] Seddall, pp 80, 83.

[77] Plunket, ‘Introduction’ to Seddall, p xv.

[78] Seddall, pp 80, 83.

[79] AJ Seymour, Reminiscences of Charles Seymour of Connaught (London: Skeffington and Son, 1895, 59 pp), pp 19-20; Leslie and Crooks, p. 613; Bowen (1970), p 207.

[80] See the various reports of the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commissions (ARCIC).

[81] Seddall, pp 11-12.

[82] ibid, p 176.

[83] Crooks and Leslie, p. 256.

[84] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 153; Leslie and Crooks, pp 363, 469; see Burke’s Peerage and Debrett’s Peerage, various eds, s.v. Decies.

[85] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 153; Leslie and Crooks, p. 613.

[86] Bowen (1970), p 103.

[87] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 77, 156-157; Leslie and Crooks, p. 392.

[88] ibid, f 80.

[89] Seddall, p 43; Whelan, p 119.

[90] Bowen (1970), p 95; Teresa McDonald, Achill, 5000 B.C. to 1900 A.D. (Doagh, Achill: IAS Publications, 1992), p 85.

[91] Seddall, pp 67-68.

[92] See Seymour, passim; Leslie and Crooks, p. 613.

[93] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 78; Leslie and Crooks, p. 303; Bowen (1978), pp 203-204; Seddall, p 117.

[94] Leslie, Tuam Ts, f 78; Leslie and Crooks, p. 93; Bowen (1978); pp 303-304.

[95] Leslie and Crooks, pp 503, 515, 616-617. [96] See Bowen (1970), pp 93 ff.

[97] ibid, p 95.

[98] Falvey, p 36.

[99] Whelan, loc cit, p 132.

[100] See Patrick Comerford, ‘A Bitter Legacy,’ in Comerford et al, p 6.

[101] Seddall, pp 128-129.

[102] ibid, p 180; Whelan, p 125.

[103] McDonald, pp 24, 85-86.

[104] Seddall, p 130.

[105] Quoted in [Edwy Kyle] Achill Mission 1834-1984 (Dublin, The Society for Irish Church Missions, 1984), p 7.

[106] do. [107] Comerford, loc cit, pp 6-7.

[108] Plunket, loc cit, pp xii-xxiii.

[109] Seddall, p 54.

[110] For a similar assessment of the Moravians see Durnbaugh, Donald F, The Believers’ Church: The Unity and Character of Radical Protestantism (New York: Macmillan, 1970, xi + 315 pp), pp 51-63, 120, 232-233, 291-292; Moravian missionaries were expected to convert people to Christianity but not to a specific denomination (Durnbaugh, p 292).

[111] Comerford, p 7.

[112] David Bosch, quoted in Patrick Comerford, ‘Halfway through the Decade,’ The Church of Ireland Gazette, 9 August 1996.

[113] Appendix compiled from Leslie’s Killlala lists, Leslie and Crooks, and various editions of Crockford’s Clerical Directory, the Irish Church Directory and the Church of Ireland Directory.

This is an edited and revised version of a lecture first presented to Scoil Acla, the Achill Island Summer School, in Saint Thomas’s Church, Dugort, on 12 August 1996. It was first published in two parts as: Patrick Comerford, ‘Edward Nangle (1799-1883): The Achill Missionary in a New Light – Part 1,’ Cathar na Mart, Journal of the Westport Historical Society, no 18, 1998, pp 21-29; and Patrick Comerford, ‘Edward Nangle (1799-1883): The Achill Missionary in a New Light – Part 2,’ Cathar na Mart, Journal of the Westport Historical Society, no 19, 1999, pp 8-22. Another version was published as ‘Edward Nangle (1799–1883): the Achill Missionary in a New Light,’ Search 22/2 (1999), pp 123-136.

Acknowledgments:

I wish to thank:

The former Bishop of Tuam, Killala and Achonry, the Right Revd John Neill (later Bishop of Cashel and Ossory, and subsequently Archbishop of Dublin), for introducing and chairing my lecture at Scoil Acla on 12 August 1996;

Mr Thomas McNamara (The Boley House, Keel) and the committee of Scoil Acla for their invitation, and many oral and family traditions;

The then Rector of Castlebar, the Revd Gary Hastings (now the Ven Gary Hastings, Rector of Galway) and the Select Vestry of Saint Thomas’s, Dugort;

Mr Billy Scott and the staff of the Strand Hotel, Dugort;

Dr Raymond Refaussé and Ms Heather Smith of the Representative Church Body (RCB) Library, Dublin, for assistance with research and access to manuscripts and books;

The late Mrs Violet McDowell of Gray’s hotel, Dugort, for access to Nangle’s painting of Dugort Strand.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

© This article is used with the kind permission of the author Reverend Patrick Comerford of Dublin.

To keep the integrity of the excellent research done by Patrick in his blog article I’ve included the page in it’s entirety, with just a little reformatting to fit it into my blog’s template layout.

* Sarah, Edward Nangle’s second wife, was Sarah Fetherstonhaugh, daughter of the Rev’d Cuthbert Fetherstonhaugh, the Rector of Hacketstown in Co Carlow, and his wife Anne neé Holmes.

See photographs of Edward, Sarah and their four children plus a few others from Edward’s first marriage here.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment